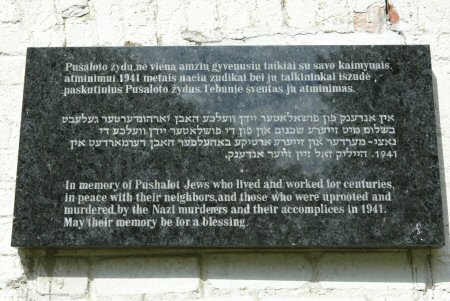

Pusalotos Lithuania

Mair Brog - His Life Story

This picture was given to me by the Lithuanian Historian with the Pasvalys Museum, A. Picture taken in 1937 by a local photographer, Petras Pranke. In the picture are pupils from the Pusalotas Jewish school, the teachers, and other young Jews who took part in. Lithuania is a country in northern Europe on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea.Lithuania is a member of the European Union, NATO, and several other organizations. About 3,000,000 people live in the country. The official language is Lithuanian which is spoken by more than 82% of the people. Vilnius is the capital and largest city. The colors of the Lithuanian flag are yellow (at the top. Lithuania is a small country located near the Baltic Sea. In 1792 the Russian Army conquered Poland and the three Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania became part of the Russian Empire. The number of citizens living in Lithuania at that time was about two million and about two hundred fifty thousand of them were Jewish.

Mair Brog was the 4 year old son of Rabbi Ruvin Brog, Gabbai of Pushelat

English Translation by - Ita Shahar

Edited by - Howard Margol

Mair Brog recorded the story of his life 60 years after he arrived in Palestine. His younger brother, Isrolik, arrived in Palestine 5 years after he did. Mair was born in Pushelat, Lithuania on April 17, 1908 (29th day of Nisan) and his brother Isrolik (Israel Mendel) was born in Pushelat on August 24, 1910 (2nd day of Elul). Their parents were Rabbi Ruvin Brog and his wife, Frada Schemer.

LITHUANIA - ITS HISTORY

Lithuania is a small country located near the Baltic Sea. In 1792 the Russian Army conquered Poland and the three Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania became part of the Russian Empire. The number of citizens living in Lithuania at that time was about two million and about two hundred fifty thousand of them were Jewish. Fifty percent of the Jews lived in the four major cities and the rest of them lived in about thirty small shtetlach. The ruling nobility owned most of the land, in full partnership with the clergy. Most of the Jews were involved in trade, or crafts, and they provided services to the whole population.

It was the time of an enlightened Tsar and it was a little bit easier for the Jews. They were able to live in the larger cities except they were not allowed to live in the capital of St. Petersburg. They were also allowed to partake in land for agriculture. As a matter of fact, here and there Jews had land in the country and were working as farmers together with their countrymen. It was like the story in 'Fiddler on the Roof', Tevye the milkman.

Most of the little towns where Jews lived were set up in the center of the villages and they had the shape of a horseshoe. The houses of the Jews were like the framework around it. In the middle was a very big square that was used as a marketplace. Twice each week the square was filled with carts with horses, with agricultural products, wood from the forest for heating, horses, cows, goats, and so on. These two days were the noisiest with everybody talking, weighing things, and near the shops everyone was busy. Every member of the family participated in the buying, the selling, to help support the family.

The houses themselves were usually built of lumber with wood in order to ensure heat during the winter. The roofs were covered with straw. The inside of the house was divided with a wall that separated the living room, the bedroom, and there was another area that was used for the stove and the heater. In a lot of the houses, the shop, or workshop was also in the house. The toilet was near the stable or cowshed in the yard. In a distance of about ½ mile there was a well with a depth of one to eight meters. The well contained a thing, in the shape of a 'Y', with a rope, to lift up the water in a bucket. Members of the family brought water to the house during all hours of the day. Whoever had time would go with two buckets and bring water. In our little town, we had a well that the gourmet people said the water tasted better. Whoever was not lazy would go a little further to that well and bring water. That water was used only for tea. In the towns where there were rich Jews they also used a professional water carrier to bring their water.

The cow had a very central and meaningful part in the nutrition of the people because the cow gave milk, cheese, sour cream, and butter. Whoever could not afford a cow had to settle for a goat. Very few also had a horse and a cart. Except for the snowy months during the winter, the cow was out in the meadow. One milking was done during the middle of the day by one of the girls of the family who had to go on foot two or three kilometers to the cow. Before evening, the cow would be brought back to the cowshed and, early in the morning, the cow would be milked again before it was taking out to the meadow. So, the cow was milked twice each day.

THE COMMUNITY LIFE

The community life of the Jews centered around the synagogue and the bathhouse which also served as the mikvah. They heated the bathhouse once a week, on Thursday, and everyone went there to wash himself or herself. They were like cleaning themselves to welcome shabbos. More than these two services a small shtetl could not afford itself. In a larger shtetl, you could also find a rabbi and a shochet.

The education of the children - in those times the Jews did not have central institutions that could train and guide. In every shtetl there was a cheder, and a teacher (Melamed), and there they studied how to pray, they studied the chumash, the torah, and the first chapters of the bible. One of the main methods of teaching the children the torah was with a leather belt that all of the teachers wore around their waist. In our shtetl, in addition to the teacher who taught the torah, praying, etc., we had another teacher who taught writing and mathematics. The teacher did the writing, with a pencil in a notebook, and the pupil would follow it with his own hand. This is the way the pupil learned to write the letters by copying what the teacher wrote in the notebook. Regarding mathematics, it was only simple addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. If a student was excellent, he could also learn fractions. This teacher, as opposed to the Melamed, was nice and smiling. The most severe punishment he gave was a pinch of the ears. What were common with both teachers were their clothes. They wore a black coat with boots in the winter and summer and both of them looked shabby and not very clean.

Very few kids managed to get from the shtetl to a large town to learn in a yeshiva. To study in a yeshiva was the wishful thinking of every kid who wanted to be good in his studies and to get a recommendation for a good shiduch from the head of the yeshiva. The custom was that a wealthy Jew met with the head of the yeshiva, when he had the recommendation in his hand from the rabbi. The head of the yeshiva was pointing to a nice fellow, sometimes he was excellent in his studies, and everything was according to the donation that this Jew would give to the shiduch. The most brilliant students knew how to get to this goal and they were also studying in the additional secular institute of the gentiles.

Life together with the gentiles - Even though they had business connections with the gentiles, the Jews lived their lives alone. The only gentiles the Jews were in touch with were the regional government like the mayor, the priest, and the policemen. Of course the Jews had to have good relations with them and they tried to do it in many different ways. Even though there was a relatively quiet period, the Jews were not entirely comfortable. They always knew it wasn't their home and naturally, there were always ideas about immigrating to places like Palestine, Argentina, South Africa, and especially to the United States where part of our family had already emigrated.

THE BROG FAMILY

The central character where my story begins is Grandmother Itsla Yaelson Brog, our father's mother. She was born around 1835-40 in a shtetl called Keidan (Kedainiai), which is by the railway that crosses the country from the regional city, Panevezys to the main city of Kovno. At the age of 16 she got married to Arieh Meir Brog. According to her, she wasn't a beauty but she was nice with long hair in a braid. As was the custom in those days, the young couple stayed with the bride's parents for a period of several years until the husband could support himself. In those years, Grandma was learning a trade manufacturing wigs. Soon enough, everyone knew her and the orders began to come in even from the near cities. She employed in her workshop about four to six girls who were learning the trade from her. Thanks to her awareness and her competence, I assume that she was the main provider of the family that developed and grew.

In a period of seven to eight years she had four children. The first one was named Tzina Riva, the second one Rochel Pesha, the third one was Ruvin (b.1873), and the fourth one was Yakov (Jacob) (b.1876). Jacob is the Grandfather of David, Sandy, and others. All of the children had a good Jewish education and a large knowledge in secular studies. At the age of thirty-five or forty, Grandmother became a widow and that is how she remained as the central pillar of the family.

THE CHILDREN'S MARRIAGES

The first one who got married was the eldest, Tzina Riva, when she was sixteen. She married to Abelson. In a short while, after the marriage, he immigrated to the United States to Pittsburgh, and after two years he sent for his wife. In the course of the years, she bore twelve children. The second daughter, Rochel Pesha also got married and immigrated to the United States. She never had children as she always had miscarriages. This was probably the reason why she separated from her husband. After several years, she remarried and lived in Chicago. Very seldom Grandmother used to receive a letter from her. The third one who got married was the son Jacob, and he married Rachel Leah Tennewitz when they were still in Lithuania. There she had her first born, Arieh Meyer, after the grandfather, the husband of Grandmother Itsla. Jacob was also the father of Elchanan.

Grandmother Itsla gained the respect of her daughters-in-law. She always knew to stand by them if she thought they were right. She used to tell us that Uncle Jacob visited her often and he liked being at her house. She used to beg him, 'go to your wife and stand in front of her as a soldier in front of an officer'. In a short while, Abelson sent for them and they also came to Pittsburgh. Jacob served as a chochet in the synagogue and also as a Hebrew teacher. In Pittsburgh, the other children were born in the following order. The second son, Victor, is Maurice's father. The third one, Israel, is David's father. The fourth one, Gitel. The fifth one, Reuben, after our father, and the sixth one, Freda, after our mother. So, the only ones who stayed in Lithuania were Grandmother Itsla and her son Ruvin. Why they didn't join the two-thirds of the family in the United States I do not have an answer to it.

Under the Tsar's rule, they were enlisted in the army service for 25 years. In earlier times they even enlisted at the age of 12 as they were kidnapped in the streets. That is how our father at the age of 20, or 22, was sent to the Caucuses. Of course, even in this regime there were many who tried to avoid the army service. There were even stories about drinking a type of tea for weeks, or other things to make your pulse beat quicker so you would not be taken to the army for health reasons. There were even cases where people used to cut their fingers on their right hand so they could not use a gun. Some even lifted heavy weights in order to get a hernia so they would not be taken to the army. Our father was not like that so he was drafted for 25 years.

For several years this nightmare went on while Itsla's beloved son was thousands of kilometers away, in the dark mountains of the Caucuses. During these three years, Grandmother worked, saved money, and prepared herself for the action of bringing her son back home. She went on an unknown road, with all of her savings on her. Her Russian was not that good but one thing she knew was that God must help her. With the money she had she felt she could achieve her goal. Indeed, after three months of a very tiring journey and looking for her son, she came back with her son and with a yellow ticket that showed he was discharged.

After returning to Lithuania our father went on with his studies and became a Rabbi. He was a well-known Rabbi for his time but he did not do it to provide for his family. In order to make a living he went to Vilna and there he studied pharmacy. When he finished his studies he began planning his future and to start having a family. We do not have many details as to how our father and mother met but we assume, as was the custom in those days, a shidduch was arranged. Our mother was an only daughter, her mother died, and she remained with her father Faivel Schemer. Faivel's financial condition was good and he manufactured various products from leather. He had a small factory, was thought of as rich, and his daughter was considered a suitable match for my father. Unfortunately, we do not have any pictures of our mother but when Grandmother and other relatives described her she was short, smart, nice, wise, and everybody sought her presence and asked her for advice. In short, it was a real shidduch.

In the period between the engagement and the wedding there was a fire in Pushelat (Pusalotas). Some of the Jewish houses were burned and, apparently, Grandfather Faivel's house was severely damaged. Grandfather Faivel, following the sudden decrease of his assets, was afraid this would bring an annulment of the engagement. In a conversation with my father, Faivel said, 'Tell me Ruvin, is everything burned for me?' My father's answer calmed him down and in a mutual effort they rebuilt and reconstructed themselves, together with the others who suffered damage. During this time the wedding probably took place and my father moved to that shtetl which was Pushelat (Pusalotas).

Because of what he had learned during the years, and since he was a well-known Rabbi and a pharmacist, he became much respected in the village. Everyone used to discuss with him and he filled the place of the Rabbi and was chosen to be the Gabbai of the synagogue. He represented the whole community. When Jews from Pushelat, living in the United States, heard what happened they sent large amounts of money to help the Jews who had suffered from the fire. The money was sent to father's address, they wrote letters to him, and he had some people with him who took care that the division of the money will be divided in the right way.

Later on, when the new buildings were already standing, another donation arrived from the United States from a Jew who wanted to rebuild the synagogue that was burned. The money was to be used for a new synagogue. The Jews in Pushelat, together with some others, asked that the money be given to them and the synagogue would be built later. My father did not agree with this idea and he said that money that was given for a synagogue was not allowed to be used for other purposes. In order to strengthen his opinion he invited the most important people in Pushelat to meet with the Rabbi in Panevezys, the most important Rabbi in the area. The Rabbi in Panevezys agreed with my father and also stressed the gravity of the situation if the money was used for something else. The discussion ended and they started to build the new synagogue.

Several years of good work for the public by my parents passed, they were financially fine, they started a family, and you can assume that they were happy. Then, a terrible misfortune happened as the hand of a murderer tore the life thread of the happy Jewish family. On the first day of Succoth, 1912 at 2:00 o'clock in the morning, two murderers broke into the house. They came with iron sticks and they hit those who were sleeping in their beds. I was sleeping in the bed with my father, was probably awake, and started to scream. They shut my mouth with a towel, hit me on the head, and went on hitting my mother and my father. Isrolik, who was lying on the side of the bed in his cradle, was not touched. Perhaps they did not see him. Grandfather Faivel, who lived nearby, could not bear the pain and the sorrow and he died three days later. Father was thirty-eight and mother was thirty when they died and she was in her fifth month of pregnancy.

The murderers were caught, tried, and sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor. After a year and a half, the First World War began, and all of the prisoners were released including them. Grandmother Itsla, who lived in Panevezys, was restless on that night and regardless of what she tried she could not sleep. She started working in her workshop and, very early in the morning, the man who had the carts came and told her what happened. She got on the cart with him and went to Pushelat. Upon arrival, she was told that my father and my mother had just died and I was the only one who was still breathing. Grandmother did not shed any tears, and did not look at her loved ones. She grabbed me into her arms, and hurried the driver to get me as fast as he could to a specialist doctor in Panevezys. When we got to the doctor, he told her he could not do anything and the only hope was, if she could get in time to the nearest hospital in Dorf, which was a suburb of Riga. This was a fifteen-hour ride in the train.

As the doctor suggested, she took me together with the two girls who worked with her, on the train. During the ride, they held me in their hands so that I would not have any more concussions in my head from the shaking of the train. When we arrived at the hospital the doctors told my Grandmother that there was not much hope because the fractures in my skull were so deep my mind was probably also injured. When she heard those words she collapsed and feinted. I stayed in the hospital for eight months.

The news that I was better strengthened my Grandmother and she felt that her destiny in life was to raise us. She accepted her fate as a command from above and did not question it. Isrolik was all of this time, with Ita Minde who was a relative of my mother. When I came back from the hospital I was already five years old. Isrolik was 2 ½ years old and Grandmother was in her eighties.

As was the custom in those days, a five-year old boy would start learning in the cheder. The wound in my head was still open and Grandmother refrained from letting me meet other people for fear that somebody would touch it and cause infection. She solved the problem by bringing a private tutor, who came every day to the house for an entire year. The doctor also came twice each week to change the bandages. One day when the doctor came I caused Grandmother an embarrassment. The doctor, for some reason, did not come on his regular time and my Grandmother was mumbling to herself, 'a cholesha doctor'. When the doctor arrived later, and he did not close the door behind him, I told him what my Grandmother had said. It was very embarrassing because she said such a thing about him that was not nice.

In spite of the motherly care that she gave us, Grandmother knew that it wasn't enough and she tried to fill in the blanks. On Shabbat evening she used to invite the grown up men from the synagogue and the Yeshiva brochers so at least one night a week we would meet men and feel a friendship with someone. The preparation for Saturday started on Thursday and went in a certain order. We had to clean and shine the brass candlesticks, which were considered as cultured candlesticks because the base was made in the shape of a small plate. In this way, the melted wax from the candle dripped onto the plate and not on the tablecloth. Each candlestick weighed over three kilos. On Friday, Grandmother did not work in the workshop with the wigs. This day was dedicated to cleaning the house, to washing us in hot water, and to prepare Shabbat dinner and all of the other needs of Shabbat.

Before lighting the candlesticks she used to dress us in our Shabbat clothes. Isrolik was dressed in a long robe that reached to his ankles and I was dressed in velvet pants, with a shirt and a jacket. We waited for this outfit for the whole week. When the time for lighting the candles came, she used to cover her head with a shawl, her hands covered her eyes, and her mouth was mumbling the blessings. I always noticed the tears that dropped on the white tablecloth.

After the Shabbat prayers at the synagogue were finished the two invited guests arrived to the house. The younger one sat at the head of the table and he would perform the kiddush and, after the meal he would sing Shabbat songs until the candles were burned out. Only the shinning from the brass candlesticks still continued to shine from the light of the small lamp that hung from above the table. After almost every festive dinner like this there was a little moment of anger between Grandmother and me. The reason for it was the fuller plate that she gave to the younger Yeshiva brocher and not to me. In order not to make me angry she would say, 'vey, vey, vey, what big eyes you have and you wouldn't be able to finish it anyway'. Indeed, I couldn't.

Isrolik was not a big eater because he had a childhood disease that made his bones soft which tended to make them break easily. It was a lack of calcium and was called the English disease. Because of that the bones did not develop in the right proportion. The head and the stomach were like big and the hands and the legs were very thin.

Saturday night, after Shabbat, Grandmother would put us to bed and she would sit in her workshop and work even until the morning. During the weekdays, friends and neighbors were visiting her and one of them was a young woman who worked in her workshop and who held me in her arms when we made the trip to the hospital. Their conversation usually was about Grandmother's destiny that by the end of the day she became a young mother and that is how God wanted it. Their conversation would end at night with a gesture of their hands toward the sky.

On Saturday afternoon, when we were napping, tired from the good cholent that we usually ate for lunch and dinner, Grandmother was sitting with her prayer siddur. Between chapters, she was like arguing with God, 'why did he do it to her, why didn't he take her instead of them, and if he needed to take someone it should have been her'. Then she would say, 'Who am I to argue with him, probably someone has sinned and probably his justice was right', and then she would close the book with a kiss, wipe her wet eyes and go on.

One day, during the first year, Grandmother said, 'children, today you wear your shabbos clothes, we are going to have our picture taken, and have a memory from your Grandmother'. We did not understand what it meant to take pictures but after several years we understood it.

WORLD WAR I

Very early in the morning, Grandmother woke us up. Sleeping at this age was probably very deep and we did not want to get up. She hurried us and told us to get dressed because we were going to Pushelat. Every day, the government issued the 'rules of the day' and posted them on the wall outside our building. On that day, the rules were already posted and the Jews were ordered to transfer, within forty-eight hours, deeper into Russia. Our Grandmother decided not to join the camp in Panevezys but to transfer to Pushelat. There, she could join our relatives so that if, God forbid, something happened to her at least we would be closer to our relatives.

Early in the evening, we arrived in the Market Square in Pushelat. There we found groups of families with all of their belongings. Eta Minda's family of three people - two sisters and a father was there. Enlarging the family to include the three of us depended on formal arrangements that could only be done in the neighboring town of Pumpian (Pumpenai). The assignment was given to Grandmother who spoke Polish and a little bit of Russian. According to the preparations that were going on around us, I noticed that Grandmother was about to leave us. I grabbed her skirt and wasn't going to let go of her. She mounted the stairs of the carriage and I was still holding on to the edge of her dress and crying. Two strong hands pulled me away from her and the carriage began to move away. I was running as hard as I could and shouting, 'Bubbie, Bubbie'. The carriage left behind a cloud of dust on the road and it was blowing in the wind. Soothing hands brought me back to the square. There I found Isrolik in the hands of Eta Minde, and he was also crying.

After three hours, Grandmother came back holding the certificate that confirmed we were one family. Since our family included two elderly and two small children our destination was the Ukraine and not Siberia. The first question Grandmother asked when she returned was, 'Der kinder hoben esen genumen in moil?'- 'Have the kids eaten anything?' (Literal translation - 'Did the kids put something in their mouth?').

The night came and, in the morning as I recall, we found ourselves in a carriage of a train. It was not a train for carrying people but just carriages that transported goods. Everyone was lying on the floor leaning against their packages and other belongings. I was at the side of Grandmother and Isrolik was at the side of Eta Minde. Her father was with a tallis and tefillim, mumbled prayers, and was nodding his head from right to left. The train was going very fast and the grownups that were in charge said the Germans are chasing us and disconnecting the rails. After three hours of flight, we stopped and there was a very sad atmosphere. Nobody was smiling. The place where we stopped was not familiar, the door to the carriage was opened, and somebody jumped out and announced that the engine was disconnected and went away.

We stayed in that place for two days and then an engine continued to move us on. After three or four hours, again the engine went away. At this time, all of the grownups that still had strength got out and pushed the carriages toward the place we were going to. This was not the last time we found ourselves this way but after three weeks we arrived on a Friday to the city of Melitopol in southern Ukraine (182 km SSE of Dnepropetrovsk; 46 50'/35 22'). We were stored in the yard of the Synagogue. The tightness was the same as in the carriage but we felt better and waves and waves of righteous women appeared, bringing with them pots of food, fresh bread, soup, and it was very refreshing. It was the first night after three weeks of traveling and shaking during which time we did not taste good food. The warmth of these unknown women, who cared for us, gave us a piece of bread, a glass of milk, warm clothes and shoes, I can feel this warmth up until today.

We lived in the synagogue about ten days and we were then transferred into a permanent house. This was an apartment with one room inside the other rooms. In the front of this huge room, there was one small apartment that the owner of the whole thing lived. Our apartment included one room, which was inside the ground, and one of its walls was covered with mold all through the year. The bathroom for all of the apartments was located at the end of the big room together with the boxes for garbage. Behind the place for the garbage was a fence, which was alongside the river that crosses the city. (Editor's note: this apparently was a large building with one-room apartments and an outside toilet).

On one of the very cold winter days, in order to save heat, we didn't open the ventilated small window that was in the chimney. The result was, the three of us fainted until the next morning. Another case was an unpleasant event that was with me when I climbed up the small fence of the bed in order to get to the ventilated window. I slipped, and fell back while holding the heavy iron frame of the window, the corner of which hit me in the forehead. The whole week I was walking around with a towel wrapped around my head.

One day, we all came down with typhus and the neighbors, adults and children, refrained from coming in contact with us. Even at the time when we were already becoming better, but still sick, the doctor visited us. He did not have any medicine but only advice to Grandmother on what we should, or should not, eat. On his next visit he encouraged us and told us she should let us eat a potato or borsht.

Eta Minde, her sister and their father lived on the same street not far from our apartment. From time to time they visited us and took Isrolik for a little while to their apartment.

THE CIVIL WAR BEGINS

While we were still at synagogue, the grownups were talking secretly among themselves that there is a revolution and that the Germans were coming closer to Melitopol. In the meantime, every few days there was a curfew and no one was allowed to go in or out. Once in a while we heard shots and the whistle of bullets in the air. Those days, we really knew hunger. There were a lot of stories that meant nothing to us because we could not understand them. There were two generals fighting against the Red Army, General Petalyura and General Anton Ivanovich Denikin who was the main general in charge. One would seize the area and, at another time, the other one seized the area. They both had consensus on one thing and that was they should have a progrom against the Jews. (The White Army of General Petalyura perpetrated pogroms in Russia and in the Ukraine during the 1917-1921 Civil War).

In one of those gloomy days, I noticed that the gate to the yard was open. I went out, I stood, and I could not see a soul. Suddenly, a carriage came by with a horse and it was full of potatoes. A few shots were heard and the horse began to gallop. One big potato fell from the carriage and rolled toward the pavement. I came closer to it, my heart was pounding, and I picked it up and covered it with my shirt and went home. Grandmother was already worried, wondering where I was, and began questioning me. When I gave her the potato, she wanted to know where did I steal it and she wanted to know every detail. At the end, she wasn't convinced by my story and said I will bring trouble to everyone. That day, she would not touch the potato. On the next day, when nobody came to complain, she made gourmet food out of it.

Another adventure that could have caused shame concerned an apple. I had a friend, a little bit older than me, whose mother was a shoemaker. She worked in a small hole, like a cave, in one of the yards near us. One day, he told me his mother promised him money for ice cream and he invited me to join him. I was very happy with his invitation, we were going to the market, and there he bought ice cream in a cone. I licked a few licks also. While we were walking between the stands in the market, most of the people who were selling there were women. They were country people and old women. The things they were selling were put in place on short boxes. Tomatoes were displayed in the shape of pyramids; they had apricots and pears, as well as apples. My friend asked me if I would like to eat an apple. When I gave him a positive answer he handed me a stick that he had in his hand the whole time. On one side of the stick was a nail and he told me, 'you simply stick the nail into an apple and run'. So, I did it and nobody chased me. I did not try this trick again.

THE JOINT COMES TO THE AID OF THE REFUGEES

Much of our hunger was relieved when public kitchens were opened that gave us warm soup and a piece of bread. Another kitchen supplied, during morning hours, a glass of milk filled with cocoa. This was for the children up to the age of five so Isrolik was entitled to this. I used to get up in the morning, take a small jar, and hurry to the end of a very, very long line. The line was as long as the Jewish exile. Grandmother used to add some water to it and make two glasses out of it. She did not drink any of it but gave it all to Isrolik and me.

Two years passed, until one morning when we got up we found Germans in our yard. They confiscated the landlady's apartment and about ten soldiers lived in it. Outside, four horses were tied and, every morning, they were taken to the river to be bathed and to drink. We the kids flocked to accompany them and they were very nice to us. One of them by the name of Hans, used to catch Isrolik, lift him high above his head, and swing him from side to side. When he put Isrolik back down on the ground he used to shove into his hand a package of biscuits. He used to say that he left at home a boy exactly like this and Isrolik reminded him of him. Of course, Isrolik was not mad any morning as long as they were around.

On one of those quiet days, we played hide and seek with the kids from the yard. We had lots of hiding places and Isrolik came running, very frightened, and told us he found a gun in one of the hiding places near the garbage boxes. The excitement was great until one of the children's fathers came out and told us to keep it a secret and not to talk about it.

On one of the summer days, we were playing in the street and a family was passing by near us. The father's hair was in a pigtail almost to his knees and the mother wore pants and had very small feet. On her back she had a baby in a back sack and four other kids were walking behind her. This was the first time we had ever seen a Chinese family. They turned into our yard and went down to the garbage boxes. After an hour, they came back from there with boxes full of mice. One of the fathers, who saw the astonishment on our faces, told us this would be a very good meal for them. We did not understand it.

This is how we adjusted to our new situation. Grandmother found a few neighbors she used to talk with now and then. Ita Minde and her sister Sarah were visiting very often and also taking us to see their father, 'Foter' (father) Chaikel. We always found him mumbling in a book and he spoke very little. He used to give us a pat or a pinch on the cheek.

I started going to the Cheder. We were about 12 or 14 students sitting very tight on a bench which went from one wall to the other. The desk was much higher than our size. When a kid wanted to go outside, and he needed to go outside, he had to go under the table and under the bench. While he was doing it, he used to get punches, kicks, stabbing with things, and whatever. The Rabbi sat at the center of the table and did not react very much to our mischievous behavior. He only told us words of education like, 'you should not do it, it is not nice, etc'. When the Rabbi had to go out, the class was the noisiest, as everyone was struggling and talking. When the Rabbi came back to the class all the kids were standing around him and pointing to the one who started it. The Rabbi used to stop, open his belt in his right hand, turn to me and tell me to approach him. He would say, 'Di Glecheley hat ich gehert fun der zadis'. (Literal translation: 'I heard your voice from far away'). The belt in his hand was very threatening. 'Rabbi, he is an orphan' one of the kids said. The Rabbi responded, 'So what if he is an orphan, does that mean he can run around and misbehave?' In the end, he used to settle up with a pinch and a tug on the ear. This is how we made our first steps in learning the torah.

Our lives entered into a routine that lasted about three years. It seemed that we became grownup all at once and I was already entering my tenth year. Isrolik also suddenly became grownup. We were speaking to each other in Russian and Grandmother was no longer speaking to us as if we were babies. We got used to the atmosphere of war, to the changes in government, and to the alarming stories that accompanied them. The Germans retreated, the White Russians were defeated, and Trotsky's Red Russians completed the conquest of the city. They explained to us that we do not have to fear them because they harm only the rich. They take from the rich and give to the poor. We were happy that we belonged to the side that they give to.

Pusalotos Lithuania

WINTER OF 1917

There were many rumors that we were going home. Again we are in the train carriage, wrapped with blankets from head to toe. We did not stop in the small places and, in the main places we stopped to get hot water and other things. At last we arrived at the station in the city of Gomel. Here Jews, men and women, who brought us loaves of bread, bagels, and artificial honey, met us. They also gave the children sweets that were wrapped in paper like the games we used to play. For the first time this week we stumbled upon a wedding paper with candy inside. In another few days we were in another large station which was called Baranavich. The lovely sight of the concern for the refugees coming back here made us feel very good. Here and there, even the old men were laughing, praying a lot, and mumbling in their Tefilim book (Book of Psalms). Paragraph

In another few days we were already in the train station of Panevezys. We threw all of our packages on the ground, jumped down from the carriage, and someone helped Grandmother to step down. I loaded one of the packages on my back, and we marched toward the carriages with the horses. Grandmother talked to the driver about the price and soon we were riding to Pusalotas, the town we had left three and one-half years ago. We passed very quickly the crosses on the side of the road and we could already see the town. Grandmother showed us the Jewish cemetery and, on the right side under the bent tree, our parents grave.

In another fifteen minutes of bouncing in the carriage we were standing in front of the house of one of the relatives who did not leave the town during the years of the war. We were very warmly accepted. It was very difficult for me to step down from the carriage because my feet were frozen. One of our relative’s grownup daughters supported me and sat me down near the very hot oven-heater in the house. Grandmother was standing near me and saying it is better if the cold from my feet would pass gradually and not near the warm heater. All of the daughters in the house were engaging in entertaining us, and hosting us, and giving us a glass of milk and bread with real butter which had the taste of heaven.

The mother of this family where we stayed the night was our mother’s cousin. They had five daughters and three sons and were considered one of the well-off families in the shtetl. All the members of the family worked, some in the shop, some taking the cow out to the meadow, and some bringing water from the far away well. For two or three days we were very welcome guests but later, we were just guests. After two weeks we were already guests of burden. Grandmother became well aware of this attitude, in time, and decided that we had to move into our own house even though it was open to the wind. No windows or doors but it was ours.

Once in a while, Grandmother took us to visit relatives and, of course, they always gave us refreshments and other things. This helpless situation continued for ten months and the war hadn’t yet ended. About five kilometers from our village there was still a German army unit. One day, we saw a convoy of Red Russians passing through the market square on their way toward the German army unit. In this convoy there were two cannons and four horses drew each one. After an hour, in the village we could hear the shots and, after another hour the convoy made its way back. Only two horses dragged one of cannons and the barrel of the cannon was missing. The next day there was a rumor that bombs were scattered around the market square. Most of the people who lived around the square closed themselves up in their houses. In the end, we found out that someone wanted to intimidate us and just scattered around a few packages of beets.

Life in those periods was not easy for people even in the good years. For Grandmother, in spite of her will power to deal and stand against all pressures, the signs of fatigue began to be seen on her. They were caused by day to day worry about our existence and our support. She was not sure if, on the next day, she would have food to serve us and especially, she did not see any purpose for us. She decided that, after the winter, we will move to Panevezys. There, she is known and she will again open her workshop and not have to rely on the help of relatives. As a matter of fact, Grandmother was disappointed in the relatives. In the meantime, she knew that she had to go on and, of most importance, was food and this was not at all simple. You could not buy baked bread. First you had to buy the grain, take it to the flourmill, and then to bake it in your own oven. For us, this process was impossible.

Somebody gave a hint to Grandmother that you could get a small amount of flour at the grinder, the man who grinds it, because from every grind there is a little bit left. The problem is how to bring it from the village that was about five kilometers away from our village. There were several ideas, one of which was to build a small platform on four wheels with a rope for pulling. Grandmother did not entirely believe the need but I wanted to prove that it was possible so I started to work on it. The tools that I possessed were a hammer and a pocketknife. It took me a whole week until I could find the rope and build this small platform but I achieved my goal. I brought about forty kilos of flour and we had bread for a relatively long time.

For the other nutritional ingredients Grandmother took care of herself. One egg each day we had from a hen that we raised under the stove. After the hen laid the egg, she used to get out and let everybody know she had the egg by “coo-cooing”. Grandmother would hurry and take the hot egg, call us, and rub it against our closed eyes. This was a sign to bring us good health. Meat we tasted only once a week, on Saturday. It was not real meat as it was the kishka, or the lung, or the spleen. The other taste of meat was in the soup, or borsht, but only from cooking the bone. In the land near our house we grew carrots, beets, onions, and cucumbers.

For the second time I hear that I am an orphan. On one of the Saturdays we went as usual to the synagogue. Grandmother was sitting in the woman’s part, which was divided by a curtain from the men’s side. We were sitting on one of the benches when it came time to take one of the torahs out of the closet and put it on the reader’s table. Grandmother was in the middle, banging her hand on the table and declaring that she would not let them read in the torah. She opened her mouth, with very difficult words of accusation toward those present and said, “how can it be that the person who helped this community with all of his heart and soul and built this synagogue, and was murdered, left orphans, and now there is not one of you who is interested in whether these kids have bread to eat, or clothes to wear, you should be ashamed”. Usually, in these cases, the Gabbai of the synagogue approached her, and promised her in his name and in the name of everyone who was present that they would take care of the problem to her satisfaction. Indeed, this is how it was until we left Pushelat half a year later.

According to Ita Minde’s stories and Grandmother probably let her in on her secret plan to stall the reading of the torah, Grandmother’s appearance in the synagogue left a very strong impression and was the talk of the day between relatives of the family for many days. Especially, they were admiring the courage and the daring of this woman.

Life in those periods was not easy for people even in the good years. For Grandmother, in spite of her will power to deal and stand against all pressures, the signs of fatigue began to be seen on her. They were caused by day to day worry about our existence and our support. She was not sure if, on the next day, she would have food to serve us and especially, she did not see any purpose for us. She decided that, after the winter, we will move to Panevezys. There, she is known and she will again open her workshop and not have to rely on the help of relatives. As a matter of fact, Grandmother was disappointed in the relatives. In the meantime, she knew that she had to go on and, of most importance, was food and this was not at all simple. You could not buy baked bread. First you had to buy the grain, take it to the flourmill, and then to bake it in your own oven. For us, this process was impossible.

Somebody gave a hint to Grandmother that you could get a small amount of flour at the grinder, the man who grinds it, because from every grind there is a little bit left. The problem is how to bring it from the village that was about five kilometers away from our village. There were several ideas, one of which was to build a small platform on four wheels with a rope for pulling. Grandmother did not entirely believe the need but I wanted to prove that it was possible so I started to work on it. The tools that I possessed were a hammer and a pocketknife. It took me a whole week until I could find the rope and build this small platform but I achieved my goal. I brought about forty kilos of flour and we had bread for a relatively long time.

For the other nutritional ingredients Grandmother took care of herself. One egg each day we had from a hen that we raised under the stove. After the hen laid the egg, she used to get out and let everybody know she had the egg by “coo-cooing”. Grandmother would hurry and take the hot egg, call us, and rub it against our closed eyes. This was a sign to bring us good health. Meat we tasted only once a week, on Saturday. It was not real meat as it was the kishka, or the lung, or the spleen. The other taste of meat was in the soup, or borsht, but only from cooking the bone. In the land near our house we grew carrots, beets, onions, and cucumbers.

For the second time I hear that I am an orphan. On one of the Saturdays we went as usual to the synagogue. Grandmother was sitting in the woman’s part, which was divided by a curtain from the men’s side. We were sitting on one of the benches when it came time to take one of the torahs out of the closet and put it on the reader’s table. Grandmother was in the middle, banging her hand on the table and declaring that she would not let them read in the torah. She opened her mouth, with very difficult words of accusation toward those present and said, “how can it be that the person who helped this community with all of his heart and soul and built this synagogue, and was murdered, left orphans, and now there is not one of you who is interested in whether these kids have bread to eat, or clothes to wear, you should be ashamed”. Usually, in these cases, the Gabbai of the synagogue approached her, and promised her in his name and in the name of everyone who was present that they would take care of the problem to her satisfaction. Indeed, this is how it was until we left Pushelat half a year later.

According to Ita Minde’s stories and Grandmother probably let her in on her secret plan to stall the reading of the torah, Grandmother’s appearance in the synagogue left a very strong impression and was the talk of the day between relatives of the family for many days. Especially, they were admiring the courage and the daring of this woman.

GOING BACK TO PANEVEZYS We gathered near the carriage and some of our relatives, among them Ethel and Sarah, brought with them baked goods for us to take on the road. In Panevezys we placed ourselves in an old wooden house that was very similar to the house we stayed in, in Malitopol. In two or three weeks, without a chance to integrate into the environment, a fire broke out one night. We were standing outside, barefoot and wrapped with a blanket, watching the fire spread and enjoying the sight. Suddenly, Grandmother shouted, “Where is the boy!” Isrolik had disappeared. She went back into our room with someone else and found Isrolik. He had simply gone back because he didn’t finish his sleep.

THE YEAR 1918

Almost a year since we came back, the war is over and a new wind is blowing. Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia got their independence. Poland took over part of Lithuania, including Vilna, which was supposed to be Lithuania’s capital. The result of this takeover was a constant strain and border incidents that often occurred. Even though there were not good neighboring relationships, deep inside the country there was quiet, stability, and a fair attitude toward the Jewish minority. In the Parliament, a Jew was elected as the Minister for Jewish Affairs. The recovery from the war was quick. The shops were filled with groceries, in the market Jewish women were standing and selling herring, and here and there a woman was running with baskets and selling self-made bagels. In the market you could get goods, chickens, eggs, and of course, all of these good things were only for the one who had money in their pocket.

The community life also developed very quickly. In the synagogue, and in the schools, you could see young men who were studying the torah; a new Cheder was opened for the beginners, and the Yeshiva for the advanced. Grandmother made an acquaintance visit with Rabbi Kahanneman, the Rabbi who in later years founded the Panevezys Yeshiva in Bnai Brak. He agreed to accept Isrolik to the Cheder and me to the Yeshiva. In this meeting with the Rabbi she asked his opinion about my father’s books, whether to donate them to the synagogue or to the Yeshiva. The Rabbi told her she should keep the books for us and he is sure that the sons of Ruvin will make use of them.

After the fire, we moved to a different apartment that was a little bit further away from the center of the city near the big Christian church. The name of the street was Saint Miriam. The owner of the house, a Polish, lived in a separate yard that was a very nice yard with green and with flowers. Except for the days he used to pass and ask the neighbors to collect the rent he wasn’t noticed. The grandmother of the family was sometimes seen standing by the fence and talking to the neighbors. During Passover, our Grandmother used to send them matzos. Like in all of our previous apartments, in this apartment we also did not have much room. It had only one small room, a corridor, and an entrance corridor that was only one meter wide. We could hardly place the furniture. There were two beds, one for Isrolik and me and the other one for Grandmother. Between the two beds there was a table that was used for doing homework, for eating, and also for Grandmother’s work. Opposite the table there was a heating oven with wood and, right near our bed there was a very small dresser with four drawers. The bathroom was outside, about twenty meters away. If we had to do what we had to do during the night, we did it in a big pot and I was the one who had to empty it in the morning.

We started to study and during the first year we already knew how to read and also a little bit of writing. When we got back home from our studies we found a meal on the table. The basic course was potatoes, herring, and bread. I, as the grownup man and the first one in the family, took upon myself the duty of the buyer or shopper. Before Saturday we always bought a chicken and I learned very quickly the rules of kashrut (kosher). I even learned how to take out the tendons from the chicken’s neck in order to make the chicken kosher. Sometimes, I used to run back to the Chochet and ask him if we were allowed to eat the chicken because I found a nail inside. In time, I became a real expert in shopping including the heating wood and Grandmother used to compliment me once in a while.

As I mentioned before, Isrolik and me slept in one bed. Our most loved exercise, in order to relieve our bones, was to lie on our back in both ends of the bed without our pillows. We would tie our feet together and press with all of our power until our feet would rise a little bit up together with the lower part of the body and the fence on both sides of the bed used to lean on me. This role of being the housewife once in a while interfered with my games and then I gave part of it to Isrolik. He not always gladly accepted it. The result was a slap on the face, wrestling, shouting, and then Grandmother used to interfere, separate us and mumble, “vey, vey, vey, Jacob and Esau”. Who from us was Esau I leave to your imagination.

When the economic situation in the country improved, Grandmother did not lack from work and she used to get up very early in the morning and, by the light from the hall lamp, did her job. Her only request from God was she would be allowed to put us on our feet until we would no longer have to rely on other’s help.

THE YEAR 1920 – A TURNING POINT AND A HOPE

A very elegant, middle-aged man appeared in our house and said, “I came to you as a messenger of Jacob Brog. He asked me to bring you to him to America”. Grandmother overcame her momentary excitement and told him that this was out of the question because she cannot see herself able to cross the ocean. He left her a sum of money and, after a week, he appeared again and asked her if there was any change in her prior decision. She was still very persistent. After some time we found out that the real reason for her refusal was not the sea but she was afraid that we would turn to be gentiles while she was sure that at least me would be a rabbi in Israel. She was afraid that there was not enough Judaism in America.

From this day our economic situation became better and better. Each month we received a sum of money and, together with the money that Grandmother earned there was a great improvement in our level of life. We could afford to eat more than enough and when you are content, and not hungry, you have a better perception of life.

The studies were not that hard. We used to bring home stories from the Cheder and share them with Grandmother. She enjoyed listening to them and, sometimes, would even smile. We told her the legend about the river that was boiling and stormy for the whole week but on Saturday it rested. We also told her about God and how through him the Tzadikim are able to perform miracles. We shared with Grandmother other stories like how the world is depending on the thirty-six Tzadikim, about ghosts, demons, witches, and stories about the next world. Also about the revival of the dead, about heaven and the seventh heaven, about the divine court in the skies, and the wonderful meals of the Tzadikim in heaven, like meals from the best bull, the white one who has the best meat and from the whale. This is the richest meal that can be served. More and more stories, both scary and mysterious, were learned in the Cheder. We used to share all these with Grandmother who showed us knowledge of herself and even added more stories about the nine seas, the falling of the temple, the ten days of Shavu’ot, the ten days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, about Yom Kippur and the day of forgiveness. We had a lot of satisfaction when she heard from us stories from the bible, about heroes, about the wars and about the victories. She was pretty sure that if we moved to America we would not have learned and known all of these good and beautiful things.

1920

We grew up in two years more. Isrolik began his studies in the Hebrew High School and I went on learning in the Yeshiva. In the year that passed, in addition to the bible we learned two chapters in the Talmud, “Baba Kama” and “Baba Matzia”, and in the third year we started the chapter of “Betah”, then “Gitim” and “Tzuvot”. Even though I was not that interested in the Talmud studying I was considered a pretty good student. I especially excelled in remembering the chapters and where they were located in the pages but not in the contents and in the interpretation as to the exact meaning. I just could not grasp or remember all of the explanations. I was the worst when we reached “Gitim” and “Tzuvot”, which are chapters that deal with relationships between him and her. An example is, when the groom, after the chupah, claimed that he found an opening in her and the bride claimed that it was from the “hit” of a tree. I, as well as my peers ages eleven and twelve, don’t understand what this is all about and what connection it has with the bride and groom and an opening of the tree. The rabbi continues and tries to explain and he says, “Let’s assume that the bride was playing and sat on a log in the same way that you sit on a horse when you ride. Then, a piece of the wood from the log, like came in.” This illogical explanation even entangled us more with mystery and fog. The rabbi, who was convinced that now everybody understands, orders one of the kids to repeat the words. Again, when the kid gets to the “hit by a tree” he starts laughing and sprays everyone around him, including the rabbi, with saliva from his mouth. Of course, everyone else starts to laugh. The rabbi gets up, lifts the boy’s chin, slaps him on his cheek, and says, “why are you making laughter out of the Torah?”. The kid goes on reading and when he comes to the same sentence he laughs and he cries at the same time. The same scene repeated itself when we read chapters that dealt with homosexual relationships.

Grandmother usually asked us, and wanted to know, what did we learn today? It seems that she was very pleased but it was very difficult for her to understand what Isrolik was studying in high school and what the purpose of all of these secular studies was. She, of course, understood perfectly the purpose of the studies in the Yeshiva. We explained to her that once you finish the studies in high school, there is a possibility to continue to study in a school where you can learn medicine, law, engineering, and other things. Grandmother said, “One thing I ask of you, don’t study to be a gynecologist”.

Pusalotas Lithuania

I continued to study at the Yeshiva until the end of the year and I am determined to leave and start to study a profession that I could make a living of. As it was the custom in those days, the trainee who wanted to study a profession worked for two or three years without being paid. In addition, it was established at the beginning the payment you had to give to the trainer for teaching the profession. For me, they also found a place where I didn’t have to pay anything with an old Jewish man who was a watchmaker. He was a specialist in his trade, a widower, who did not want to live with his children. He used his reputation in his trade and accepted clocks with very unique problems to repair. He specialized in antique clocks and owners who had sentiment toward their clock and they did not argue with him about the price of the repair. This is how he made an honorable living.

The compensation that I had to give for not paying the training fee was that every Thursday I went with him to the bathhouse. I would carry the bag containing the clean laundry and the towels. In the bathhouse, he was considered a personality, they were saving for him the leaf broom, and they were pouring new water on the hot stones so there would be better steam. My job was to hit him with the broom on all sides of his body until he said, “enough”. I would then help him down to a recovery room and he used to say that he enjoyed my slaps with the broom.

In the area of work I made advances quicker than it was expected. In those days, we developed a thirst for knowledge. Isrolik was telling about his studies and about what was going on in the high school, about the teachers and about the educators. This was not at all like they used to teach in the Yeshiva. We started reading books that were not allowed and also the newspapers. We especially liked geography and Jewish history. We got a map of Europe, hung it from the dresser in our room, and we used to test each other in the knowledge of capitals or countries, and about rivers in various lands. Of course, no river, not the Mississippi in America, the Nile in Africa, or the Volga in Europe could reach the power or the strength of the Jordan River in Israel.

Before the end of this period, in the Yeshiva, we listened to two sermons. One was of the very famous Magid (fortune teller) who could make the women cry. The contents of this sermon were the life of the man in this world that resembles a huge chandelier with many, many candles that is hanging above our heads. ( Translator - Snip, snip…the description of the second sermon could not be translated). This is how a chapter in our life ends and a new era begins which is very different from the one before.

1921

It is the year 1921, I am of the age of Bar Mitzvah, and Grandmother bought me a pair of Tefillim. She invited to our house a fellow from the Yeshiva in order for him to teach me how to use it. In the pastry shop where we bought refreshments for our guests, we bought some cookies. At the end of each lesson, I used to pray on the Tefillim. Grandmother was always excited at this event and she was grateful to the Lord who had mercy and pity on her so she could experience this moment. Isrolik was not there because he was in school.

During those first steps toward a new way of life, it was difficult to describe that in such a short time we stopped feeling the past. Grandmother was aware of the change we went through, but she did not mourn over it, and she adjusted to the new situation together with us. It was obvious to her that neither of us would become rabbis.

In one of the days after the Bar Mitzvah we had a visit from Ethel and Sarah and a student accompanied them. Sarah was a beautiful girl, at the age of 15 or 17, and my grandmother questioned whether the student was a groom. She told them that I was studying some kind of a vocation, or trade, and Isrolik was studying Hebrew, the holy language, in the high school. The student also participated in the conversation and Isrolik showed him his ability in poetry, and in singing. Ethel patted Isrolik on his head and the student left a present.

After several weeks, they appeared again without the student, this time to say goodbye. They were leaving for America to meet the two older brothers who were already there, even before the war. The separation was very sad. Ethel said that yesterday, they paid a visit to the cemetery and said goodbye to their mother, and to our parents. We were all crying, except grandmother, and we said we hoped they would cross the sea peacefully and with hope. All those they had visited the day before, who had already died, would be there and would speak to God on their behalf. Ethel hugged Isrolik and mumbled, “Oh, how much this boy is planted deep in my heart”. This is how the closest relatives we had disappeared. During future years we received several letters from them and, inside each letter there was five dollars.

THE WINTER OF 1921-22

This winter was described as a hard winter. They were talking about two degrees centigrade and sometimes more. We, the young ones, did not feel it as much and we went on with the routine of our everyday life. I agreed with my employer that I would arrive to work two hours later. I wasn’t paid for my work anyway, in the meantime, because I was busy helping grandmother in the housework. I used to fix things, I used to do the laundry, light up the oven, bring water from the well, preparing meals, and shopping.

This was the first time I saw a dead person in front of me. The manual pump that we used to pump the water was in the square in front of the church. There was always a line there of people from all around. More than once I saw people filling two buckets, starting to walk, slipping, falling, and starting again. The ground around the pump, including the pump itself, used to be one piece of ice. In one of those winter days, there was also thunder and lightning. A woman with a big belly had her bucket near the pump, she took the handle, and after two or three pumps lightning hit her and she fell and died. Her face became blue and somebody from the line shouted, “You have to put the bottom part of the body in the ground and, in this way, the lightning will come out”. I was very frightened and scared and went back with the two buckets of water. Grandmother said, “even if we do not have one drop of water in the house I do not want you to go to the pump in such weather”.

Even though we had a lot of work in the house, and at work, we always found some time to go to the frozen river. There we would watch, not without envy, lots and lots of young boys and girls, by themselves and in pairs, parents with their kids, skating on the ice and enjoying it, and we could not taste that taste. We were content with the very little free time that we had, and we used it to read books. Books by Sholem Aleichem, Mendel the Book Seller, Bialik, Mapu, and more. Once a week we went together to the library, which was quite far from our house, to read the newspaper. We were reading a different chapter each week of a story that was written by Victor Hugo, in Hebrew. We also read the books by Jules Verne.

One of those cold nights, by the heated oven, we felt like tasting chocolate but this was something we could not afford to buy as this was a product brought from Switzerland. We consulted with grandmother and we decided that the ingredients of chocolate were cocoa, sugar, and milk. These ingredients we did own. We mixed them in a pan and we put the pan on the stove but chocolate did not come out of it. In those long winter nights, we sometimes used to read papa’s books. Even though long ago we read the text from religious books we are not praying more except on Yom Kippur. This we did for the sake of grandmother. The Tsitsis we used to wear when we were kids, we did not wear anymore.

We liked to go through the books, especially the Rombom (Rabbi Moses ben Maimonides) books with the very fancy covers. The famous Rohm Publishing House in Vilna published these books. We liked as well two small books, the Babylon Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud, and other Jewish religious books. From the foreign books we read mainly the professional ones. They had very thick dictionaries, half red and half blue, English and Yiddish, Yiddish and English, and another dictionary of English and Russian. You may say that we were very pleased with ourselves, and with our ability to integrate into what was happening in the Jewish environment.

It was a period of revival that came after the Balfour Declaration. The Jew began to feel proud and walk with his head held up. All kinds of movements began to organize themselves as it used to be with the Jewish people from the beginning, Liberals, general Zionists, the Public Party, Mizrachi, Politzion, Communists, as well as other political parties. In the field, the most popular Zionist stream was the Halutz. They were dealing with transfers from the very Jewish professions into more productive professions that were more connected to building Israel.

Most of the youths that were still studying focused on and were members of Maccabi. There, they could show the goyim that the Jew is not the fragile, weak anymore who gives in so easily. In those groups, we were also with the swimming groups. Since I did not have to prepare my work I devoted myself to Maccabi with all of my heart and soul. I was among the best in sports, exercises, and I could master all the different equipment like the exercise bars, the horse, and I also played soccer.

At the age of 15 I received the title of sports trainer and I went to a small shtetl to organize a group there. I organized all kinds of sports and also raised money to purchase equipment to be used for training. While doing this it was my first opportunity to travel in an automobile that was used for five passengers. In order to shift gears in this car, there were like sticks from brass, they were shinning, and they were outside the cabin of the driver. What it meant to shift the gears I only understood after awhile.

Isrolik, during this time, was occupied by studies in the high school and preparing homework and he couldn’t take part in all of these sports activities which took place outside the school hours. It could have been the most beautiful period for us but it wasn’t like this. Grandmother began experiencing signs of weakness and she needed to rest very frequently. My help alone was not enough anymore and we needed to hire a woman to help her. At the beginning we got a girl, at the age of 16 or 17, from a village Jewish family whose parents wanted her to know the big world. This girl had no experience in housework and grandmother very quickly decided that she wasn’t qualified enough for her very modest requirements.

After awhile, a woman came to us, a mother of eleven children and very fat. She used to work and talk, but always to the point, and grandmother was very pleased with her. In two hours she managed to cook, make laundry, and clean. Sometimes she worked while her daughters helped her. Her husband was a painter. He used to walk to work, from house to house, always accompanied by two or three of his sons who carried the ladders, the buckets, and the paint. This help in the house added to several hours of worth to my grandmother and she could devote herself to knitting, especially socks and gloves from wool. Towards the coming winter, this was a nice work to do. This took some of the pressure from me also and I could enjoy the sports and social activities.

We visited the first time in a cinema and the movie that we saw was with the comedian, Max Linder. We laughed and laughed. We also visited the theatre and there was a group there by the name of Streichman, the main actor in the group. They showed the plays, “The Dybbuk”, “The Witch”, “Yosse the Calf”, and also “The Treasure”. It was a nice feeling, we got a drift of the songs, the rhymes, and it was a nice day. Even today, it is nice to sometimes repeat them in the Yiddish language the way we remember it. We also told grandmother about all of those experiences we had but this had no impression on her. However, she was pleased that we were having fun with all of this nonsense.

THE 11TH OF ADAR – THE DAY TRUMPELDOR WAS KILLED In 1923, there was a small Jewish settlement in the Galilee of Israel. There were about thirty Jewish youths there, most of them from Europe. One day, Arabs attacked them and twelve of them were killed. The leader of the group, Josef Trumpeldor, was wounded in the battle and he had only one arm. Before he died, he said, “It is good to die for our country”. We did not know if it was just a myth but it was a good story. It was a blow for the hope of Jewish settlements in Israel. The news about the death of Trumpeldor, and his friends, while they were protecting the settlement of Tel Chai caused sadness in all of the Zionist youth movements. However, it made us stick even harder to our beliefs and hopes. Very close to this incident, Vladimir (Zev) Jabotinsky, one of the most well known Zionist thinkers, came to visit. Even today his beliefs are still engraved on the flag of the “right” movement in Israel. One of his most famous sayings was, “if you do not kill the exile, the exile will kill you”. This was many years before the Holocaust. The city was decorated in celebration of his coming, many people came to the hall where he was supposed to speak, and kids from Isrolik’s class presented him with flowers. Jabotinsky’s speech was in the Russian language, there was silence in the room, and you could hear his voice even if you were seated in the last row. They said he was considered to be the third best speaker in the world, after the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, and Leon Trotsky who founded the Red Army in Soviet Russia. The impression he left on all of the attendees in the hall was very strong. For many days the Jews kept talking, arguing, and discussing his speech. The admiration for him weakened after the agreement he had with the Polish ruler to drive Jews out of Poland. Jabotinsky felt that would force more Jews to go to Palestine. Jabotinsky did not have that much influence on the youth movement. There were some local groups who talked about his concepts and ideas. These were mainly young boys from rich homes who did not have to work. They were always at the beginning of the line and were always the first to take pictures of him. They were also the ones who carried the flag of revisionism. This is how it was in our city. In larger cities, their influence was even greater. This is the way in which we grew up in 1923. I had a constant letter connection with Uncle Jacob in America who, interesting enough, wanted to know more and more about out life and plans. When I wrote to him that we want to leave Lithuania and go to Israel, he replied, “I am not against it but it is not clear to me what you will live on”. He did not think much of my profession and indeed, he was wise in his estimate. Again, he brought up the old idea to come to him to America. Meanwhile, Grandmother was two years older and her moments of weakness were more frequent. One day she said to us, “Kids, I feel that my days are limited and I ask you to take care of one another”. When we heard those words, we began to cry and I went to bring the doctor who lived nearby. He knew Grandmother from his previous visits and he tried to calm us as he began his routine checkup. The pulse, the heartbeat, and at the end he determined that the situation does not need to worry us as it is only a typical weakness for her age. He prescribed drops of Vallion (Valium) and said she needs to eat more to get more strength. After the instructions from the doctor, we always gave grandmother the first bowl of soup that had the most fat in it. We bought for her in the bakery cookies that melted in the mouth when you drank tea with it. Indeed, after several days, she was back to normal and was doing her everyday chores and things. As much as she needed us to be with her, we had more and more problems and events that pre-occupied us. More than once we were busy with our things instead of being with her but she did not complain. She understood that we could not exclude ourselves from all of the good and beautiful that children of our age need to get. Sometimes, she mentioned to us when we came home very late that she couldn’t get down to take a cup of tea. Only after several years did we begin to understand the guilt that we felt. The result was we did not repay her in the way that she deserved. THE YEARS 1923-24

Years of dreams came true – we bought an old bicycle. When we used to look at the other kids who had bicycles, we used to envy them. We had to just settle for renting bicycles for half an hour for a payment that we did not always have. We learned how to ride a bicycle by using our friend’s bicycle that let us have just one round. It was not that enjoyable because we were always afraid that we may damage their bicycle. One day I rented a bicycle for half an hour, a new one that no one had ever rented. The person who rented the bicycles told me to take good care of it and not to damage it. Since I did not know to ride too well, I was riding too fast, and I bumped on the wall of the church. The result was, the front wheel was bent into the shape of an egg and I had to put the bicycle on my shoulder and go back to the shop. The shop owner said, “Oy, Oy, Oy, what is going to be now, it will cost you five Lits which is a lot of money”. When I told him I did not have this kind of money and could I bring it to him the next day, he was not satisfied with this promise. He put his hand into my shirt pocket and pulled out my watch which was the only valuable thing I had as collateral. When I told grandmother about this, she took out her purse from her apron pocket and gave me the money.

Since then, a year passed until we bought the bicycles. There weren’t any happier people than us. With those bicycles, together with two friends, I did my last trip in Lithuania. We passed through many shtetlach on small roads, through villages, and forests. I was in excellent shape and I was never tired. This was the period when the idea of going to Israel was “cooking in me”. The incentive to do it came from the Lithuanian government who issued an order that forbid eighteen year olds to leave the country before serving in the army. There was no choice as we had to get out of the country as quickly as we could.

I started to write letters to Uncle Jacob in America, explaining to him the difficulties that were in my way. First of all, the fee, and secondly the certificate that everyone needs to enter Israel. The British government had a small amount of certificates that were mainly for older people who had already gone through training in the Halutz – the Zionist movement. This involved agriculture and other trades that would be valuable for building the country. Also, it was for those who were close to the people who were dealing with the Aliyah. My Uncle told me he had connections with Jerusalem and he hoped to get me a positive answer very soon.

My Uncle’s response gave me strength and hope and I decided to change profession and learn electricity to be an electrician. In order to do so, I went to the capital city, Kovno, where a second cousin of my mother’s family lived. They accepted me with kindness. The head of the family, who was my father’s age, was a neighborhood Rabbi. The community itself was on the terrace of the mountain overlooking the Nemunas River that was crossing the city. Nearby was the tent where the writer, Abraham Masul, wrote his famous book, “The Love of Zion”.

On Saturdays and holidays the Rabbi gave his sermons in the synagogue and he always talked about Israel and Keran Kayemet (the foundation that brought men into Israel). After the praying and the sermon, we used to go back home. Together with special people from the city we used to drink wine, taste the chopped herring, and then everybody went home. In one of those tastings, I also participated and drank a glass of wine. I was not prepared for the terrible burning that I felt in my mouth, and I got tears in my eyes. All of the attendees felt my embarrassment, even though I pretended that I did not care. I learned my lesson and, for the last sixty years, I never returned to drink a glass of wine that strong.